The latest research by The Centre for Aging better, State of Ageing 2025 report finds that living in the poorest parts of England can cost you almost five years of your life.

We will be focussing on, and discussing the report findings in more detail over the coming weeks and months but you can click on the button below to read a detailed summary.

Health

Both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are lowest in the poorest places in the country, and these places are more likely to be in the North and urban in nature. Moreover, life expectancy is lowest in places with the biggest gap in life expectancy between richest and poorest, and highest in places with the smallest gap in life expectancy between richest and poorest demonstrating the damaging effects of inequality itself.

In the three-year period to 2022, life expectancy declined in England as a whole and in each of the regions, a trend that has been attributed to austerity. And although it has undergone a slight improvement in the latest data, it has still not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Healthy life expectancy in England has shown no such improvement and has instead continued to decline. This means, we are spending ever more of our lives in poor health. At the same time, inequality in life expectancy has increased in England as a whole and in all regions except the South West.

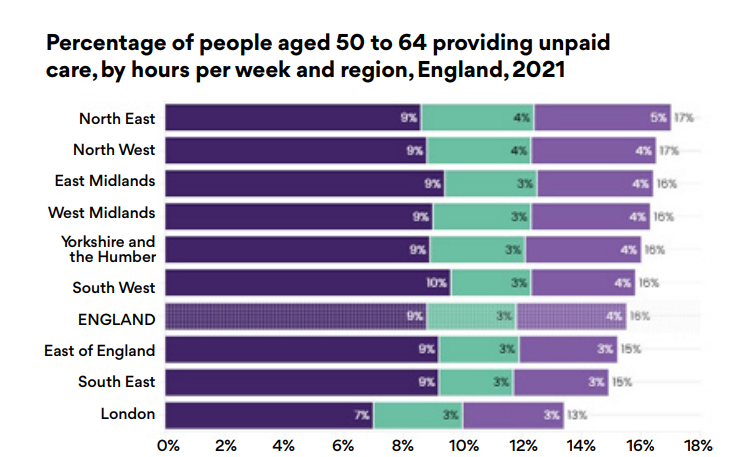

In areas with higher levels of poor health and disability, the demands on unpaid carers are greater. In the North East almost half of unpaid carers aged 50 to 64 provide 20 or more care hours per week, while in the South East almost two-thirds of unpaid carers provide less than 20 hours per week.”

Older women from minority ethnic communities are particularly likely to provide more than 50 hours of unpaid care per week. Although coastal and rural areas in England are the oldest and fastest ageing places, it is in urban areas and parts of the North where older people experience the poorest health, have the lowest life expectancy and need the greatest levels of care.

This means that national government, regional partnerships and local authorities must pay close attention to the specific attributes of local places when considering how and where to allocate resources. Although the Chief Medical Officer’s annual report for 2023 highlighted places in the country with the largest concentration of older people as those with the greatest need, we show that the oldest and fastest ageing places in England are not necessarily the places with the worst health. There are many rural places with an older-than-average age structure but better-thanaverage health. Conversely, there are many places with a younger-than-average age structure but worse-than-average health. Therefore, allocating resources solely on the basis of the size of the older population will not address these inequalities between places. In fact, to do so runs the risk of actually increasing health inequalities.

What needs to happen...

National government: Reduce the huge gap in healthy life expectancy through a Commissioner for Older People and Ageing to ensure that older people’s needs are considered across measures to build a healthier nation.

National government: Invest in local public health services that tackle health inequalities and reduce costs and pressures on the NHS.